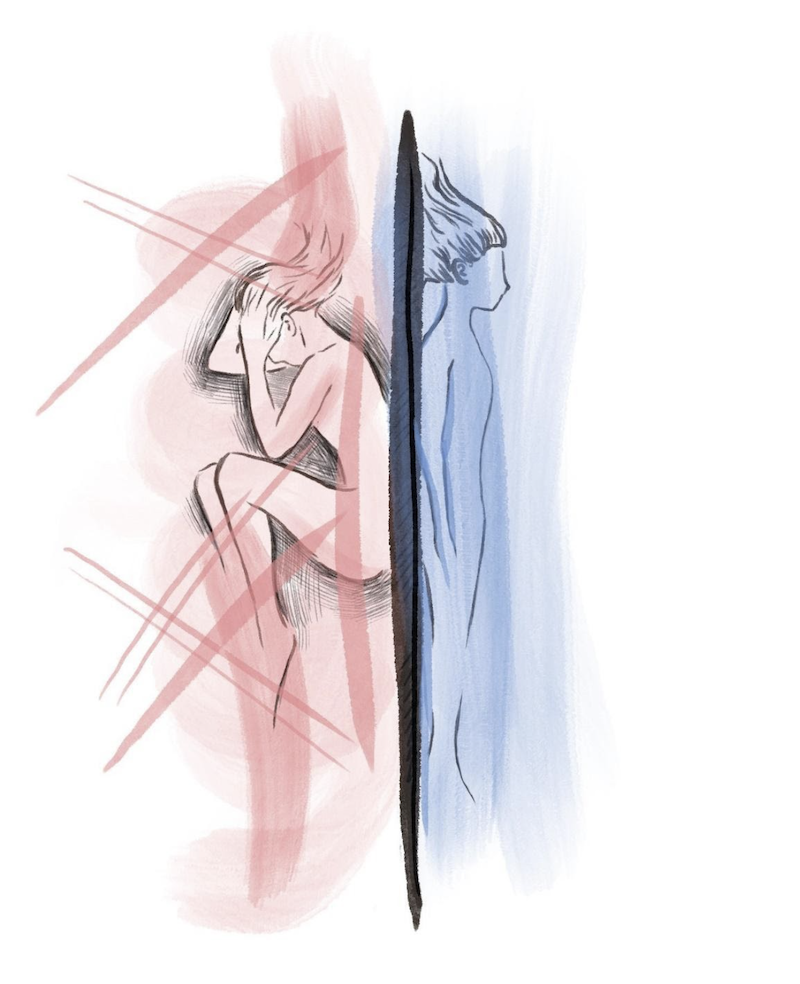

Category: Artwork2021

Xin Xu (she/her)

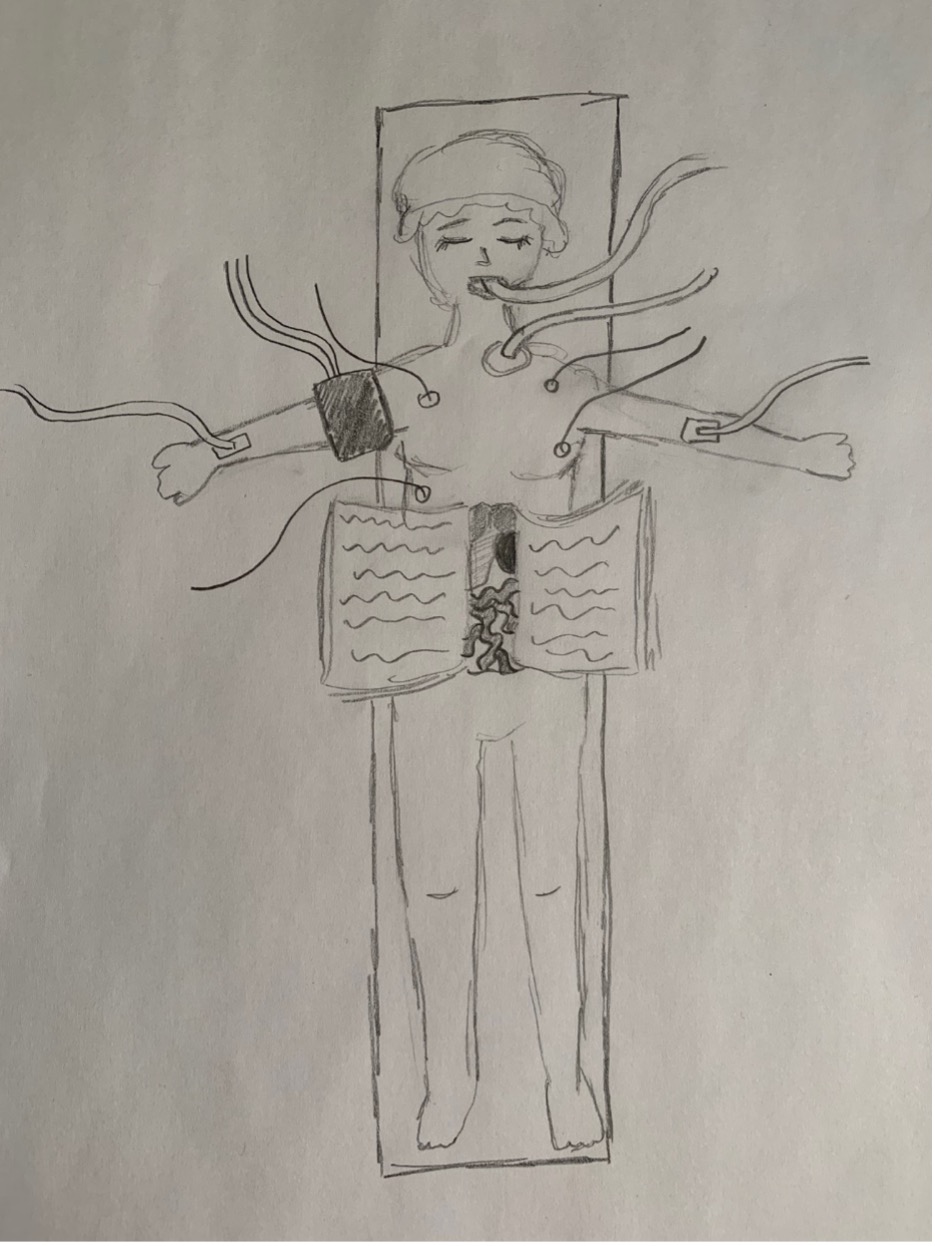

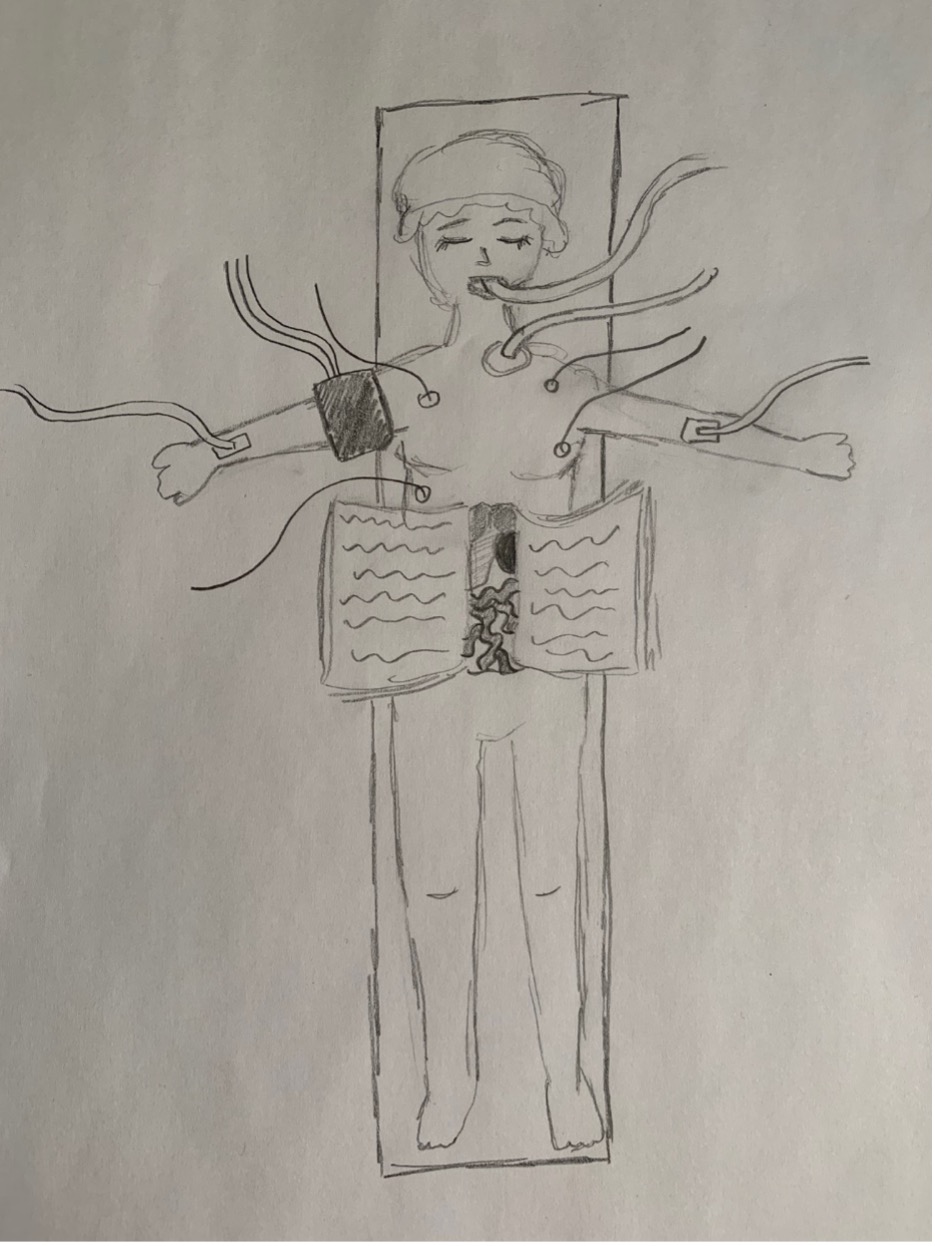

Description: There is always vulnerability present in every patient-physician relationship. In surgery, there is the additional vulnerability of patients in the operating room – laying bare, often unconscious, and trusting their surgeon to see and alter parts they often have not seen themselves. We have seen numerous patients walk into the operating room: some smiling, some stoic, some cracking jokes, some in tears, and some asking us to take good care of them. No matter how they may outwardly present, I wanted to capture the vulnerability underneath while they are lying on the operating table to highlight that we do not always see their fear or anxiety, or their deeper scars and stories.

Xin Xu (she/her)

Humanism Reflective Art Pieces – Rotation A

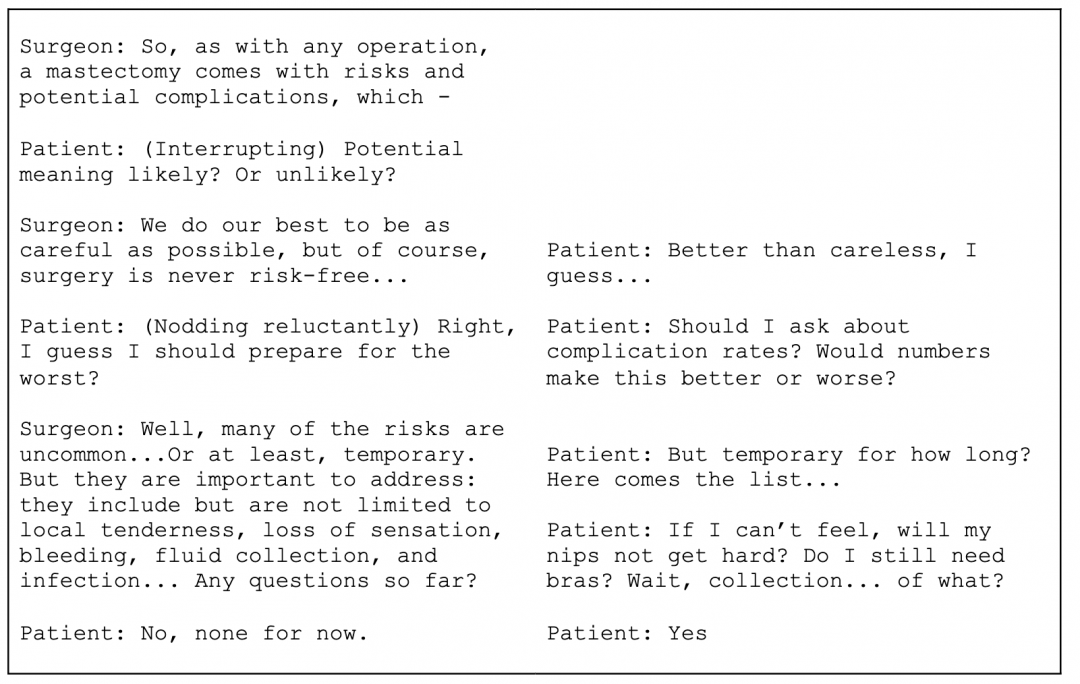

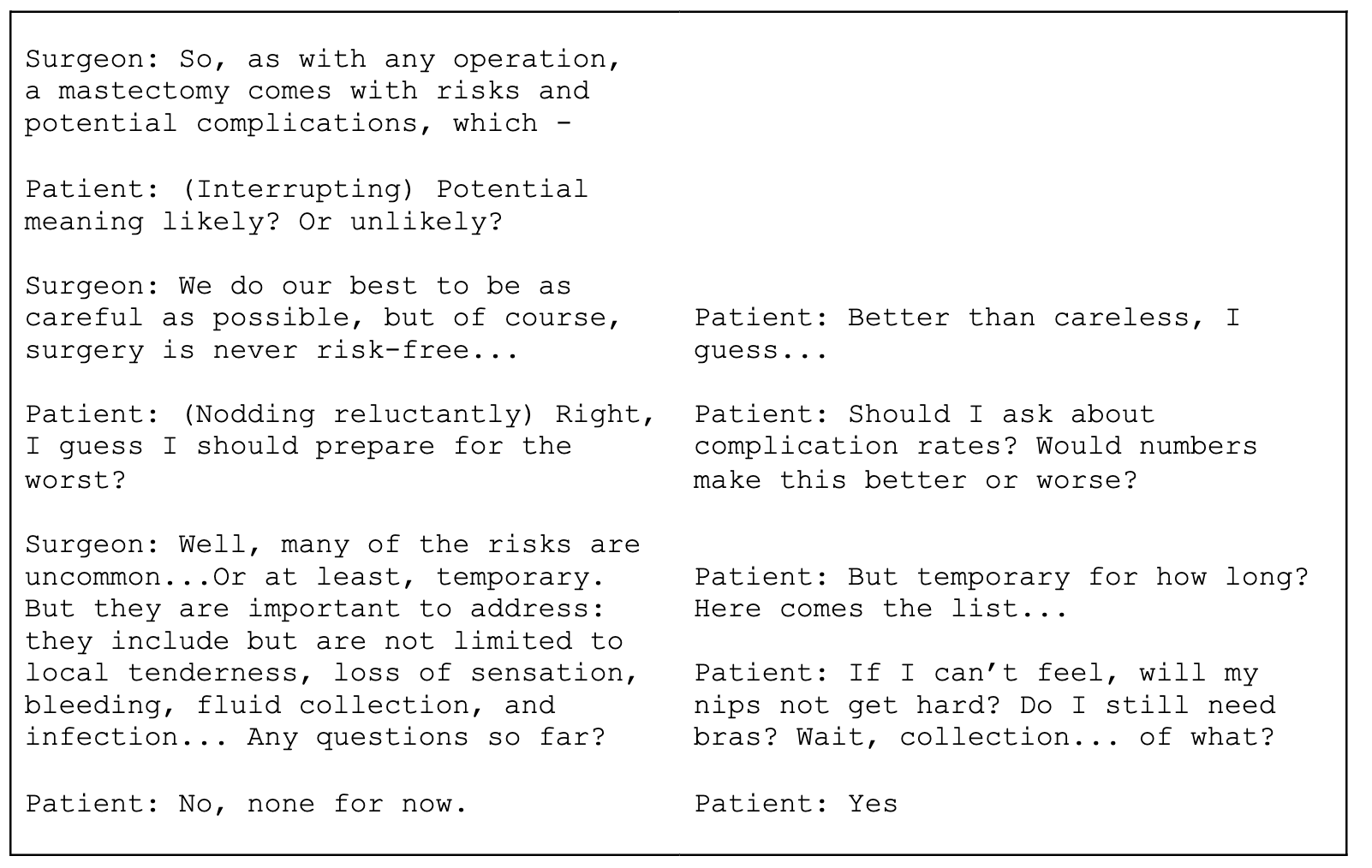

Inspired by Margaret Edson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Wit, this fictionalized script juxtaposes the “checklist” requirements for obtaining surgical consent (on the left) and the hidden concerns of an individual anticipating surgery (on the right). From the conversations we have been privy to throughout our rotation, we were compelled to imagine and compare what healthcare providers might explain (re: the procedure, its outcomes, risks, alternatives) versus what patients might wonder (re: its impact on their day-to-day).

Jason Baek, CC3

Seungyeon (Valerie) Kim, CC3

Mranali Dengre

Humanism Workshop #3 Reflection

Medical Students are really privileged to have the luxury of spending more time with patients than residents or attendings but also being able to participate in the surgical team’s activities. I think this gives us a unique perspective into both the experiences of patients and the lifestyle of surgeons. We’re able to appreciate how busy surgeons work and the burnout associated with working 1-4 call shifts (sometimes even more). However, we can also better understand how a patient feels when they’ve been waiting all day to see their surgeon and the surgeon only spends like 5 minutes with them during rounds (sometimes even less).

During my rotation, I’ve noticed several times when patients would become so happy to see the residents in the morning, but the residents would only be able to spend a few minutes with them. Seeing both perspectives I could appreciate everyone’s priorities. As a medical student, since I had a lot more time than the residents, I would sometimes go back to see some patients after rounding to chat with them and try to answer questions that I could – or write the questions down to ask the residents later and convey the information back to the patient. I think this was my small way of trying to ease patient anxiety. I think this has really shown me the value that patients place in their healthcare providers and how much anxiety we can relieve by just taking another 5 minutes to speak with patients that have a lot of questions. Going forward in my career, I will try to manage my time and schedule in such a way that I can spend the necessary time with patients that they require it !

Mranali Dengre

Julia Dmytryshyn

Every patient has a story and our interactions become a page in their book.

Julia Dmytryshyn

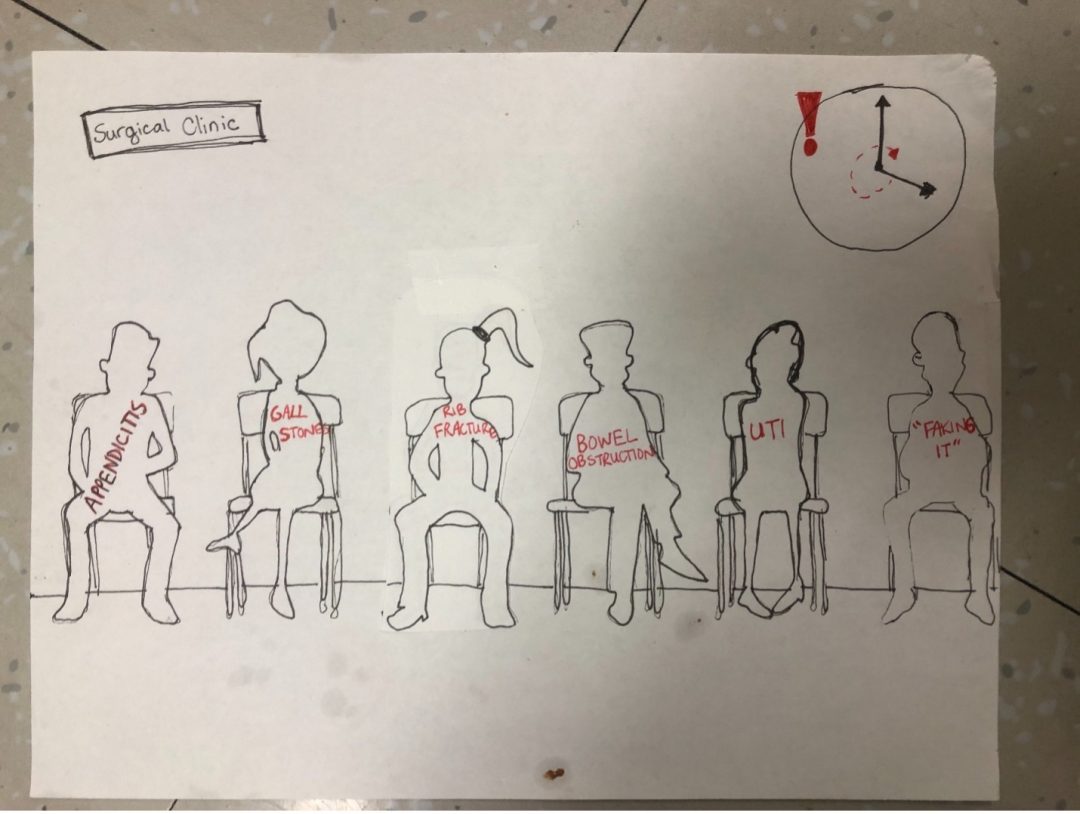

Irtaza Tahir

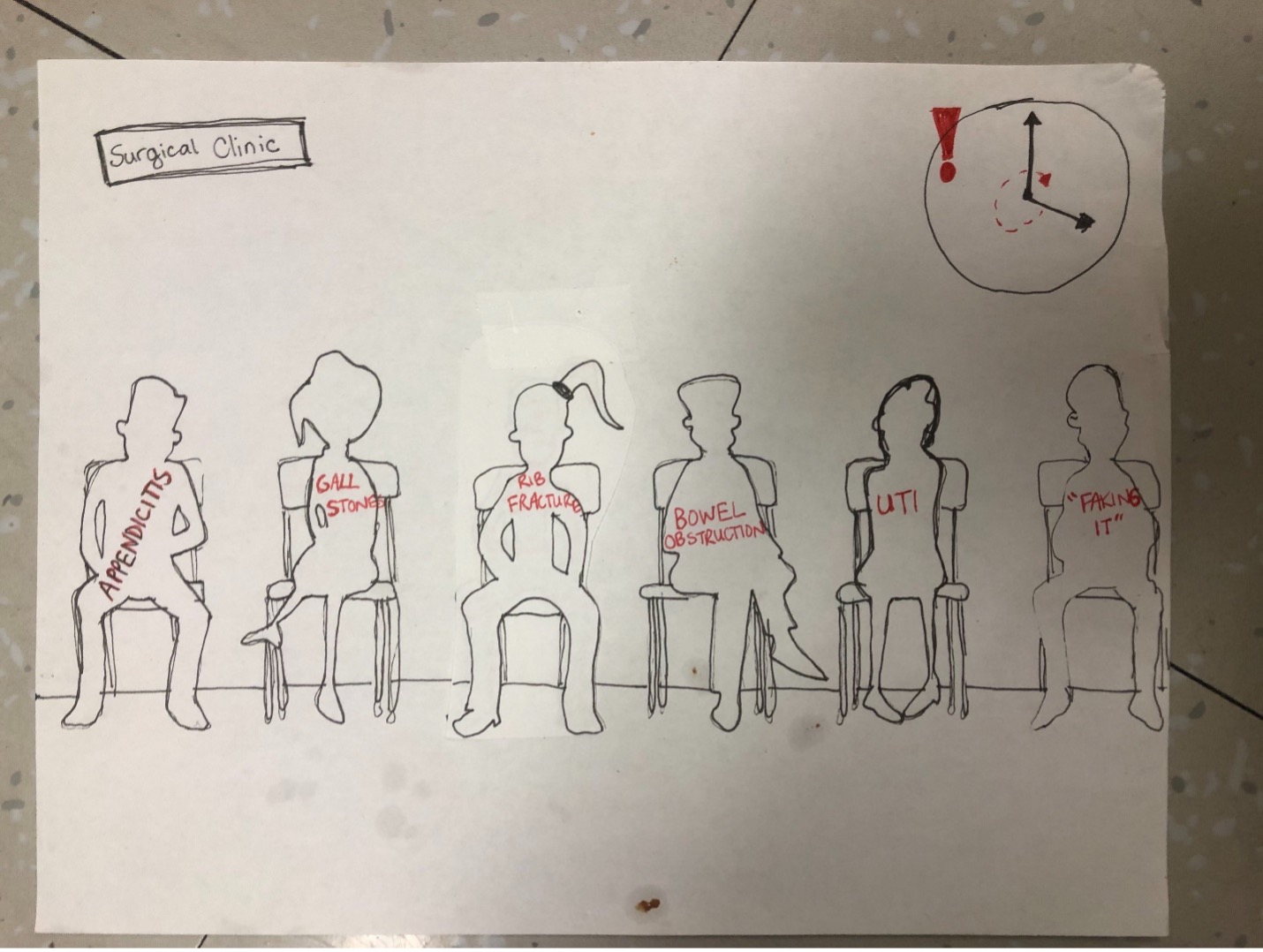

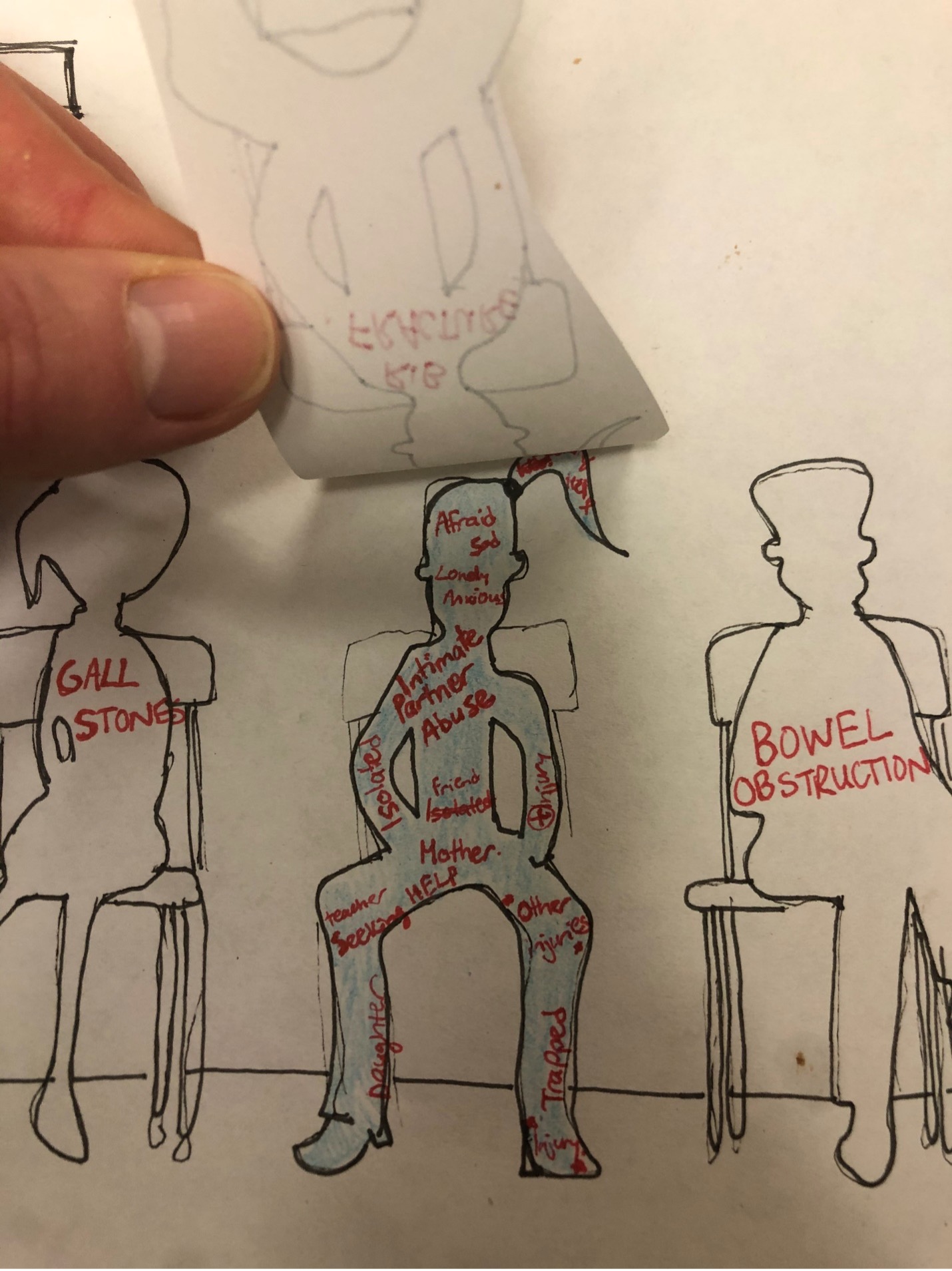

Summary:

This piece is about how patients are more than a labelled diagnosis. Often patients can be referred to as the “broken rib” and time constraints in busy clinic days place systemic barriers on how thorough histories may be. However, it’s important to remember patients are more than their diagnoses and lead full lives outside of their clinical problem, some of which can have direct implications to their presentation.

Jacqueline van Warmerdam

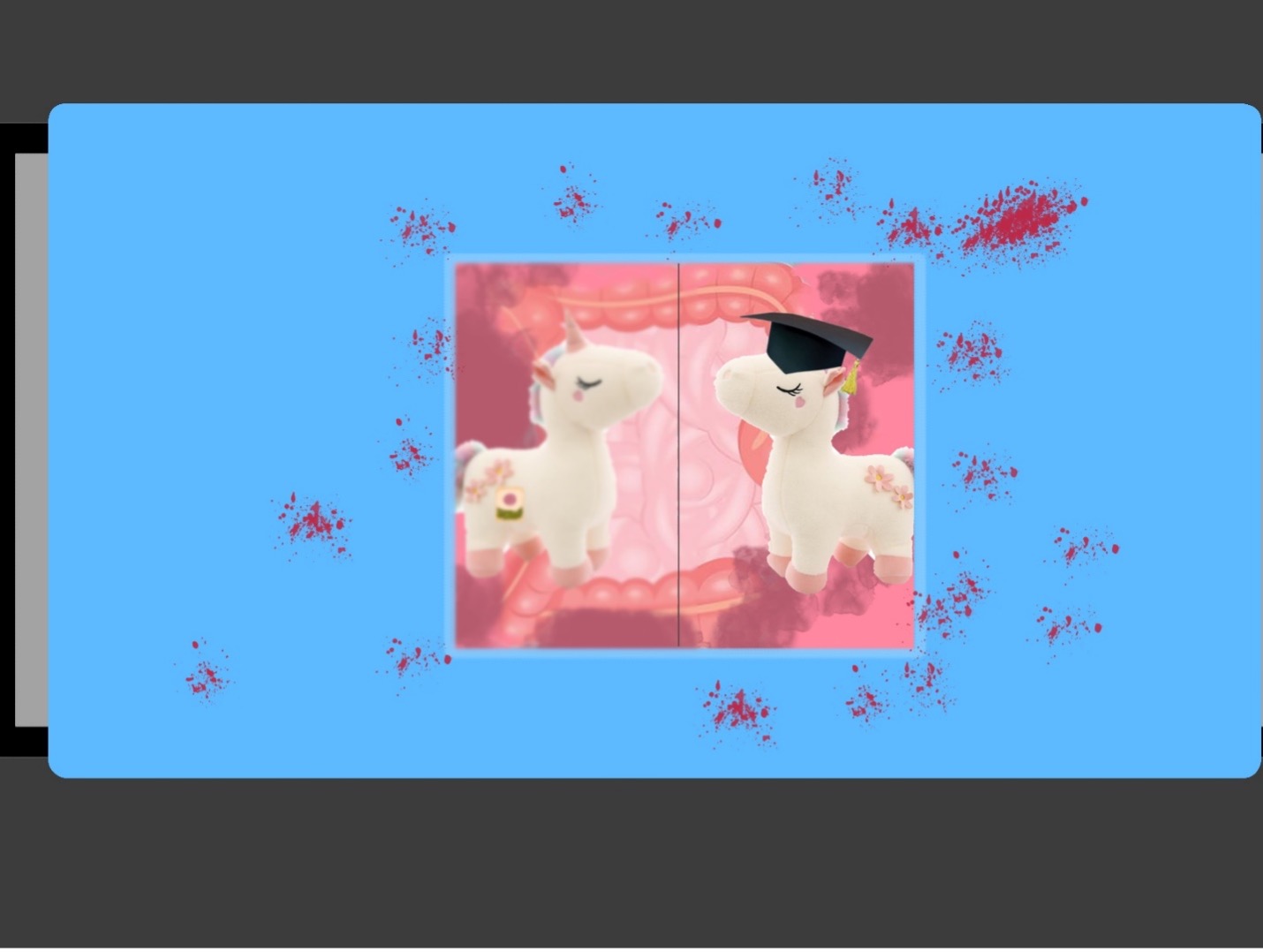

My piece is about the importance of communicating with a patient about a patient’s life story and personal goals and hopes.

The piece was inspired by two young patients during my general surgery rotation who were 19 and 22 respectively. I was on a colorectal service and these were patients who needed total procto-colectomy for UC and ileostomy creations.

The first time I often saw the patients was when we were briefly reaffirming their consent in the pre-op unit before their transfer to the operating room. You don’t necessarily know who they are and what their goals and hopes are.

It was only through speaking with patients, often post-op that I personally learned about their specific goals and fears.

The 19 year old had hopes to enter University next year and she wondered how this would impact her care. Especially given that she had severe nutritional deficiencies requiring PICC/TPN. The unicorn itself reflects her as during her stay her family brought her several unicorn plushies. The plushies also really humanized her for me as it reminded me of my sister who is of a similar age and also likes plushies.

The 23 year old is graduating this year. She likely had significant adjustment disorder. For instance, whenever we assessed her stoma, she would close her eyes and totally reject the idea of having a stoma. Because of this there were some allusions around how she was a dramatic or difficult patient, but it ended up being that she was planning to get married in the next year.

In many cases these conversations end up being useful as they determine what kind of allied health services can be involved in their post operative management. For instance, we decided to consult a dietician for the first patient and Psychiatry for the second patient.

Irtaza Tahir

Rachel Lee

This piece is a reflection of my experience with patients living with breast cancer. Over the past few weeks, I have been able to participate in the Breast Health Clinic which is often involved in the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of breast cancers. In my interactions with patients, I have noticed that there are many different reactions to a new diagnosis of malignancy. Some patients are very subdued and stoic, while others outwardly express their disappointment, fear, and uncertainty. During these brief exchanges with a patient, it is often difficult to predict how that patient will feel in 5 minutes, 5 hours, 5 days, or 5 weeks from our interaction. Will this conversation be repeated in an endless loop in their mind throughout their car ride home? Will they lie awake at night, wondering how they will break the news to their close friends and family? Will this diagnosis impact their self-confidence, self-worth, or identity? I chose to use 12 white cancer awareness ribbons arranged as the hours on a white clock face, with two intravenous catheters as the hour and minute hands. This symbolizes the cyclical and lasting impact of a cancer diagnosis on the lives of our patients, and the relative brevity of interactions with the healthcare system. My experiences have stressed the importance of being mindful and present for each patient interaction, because it represents a sliver of time in their journey.

Rachel Lee

Humanism Seminar Series

Kathleen Simms

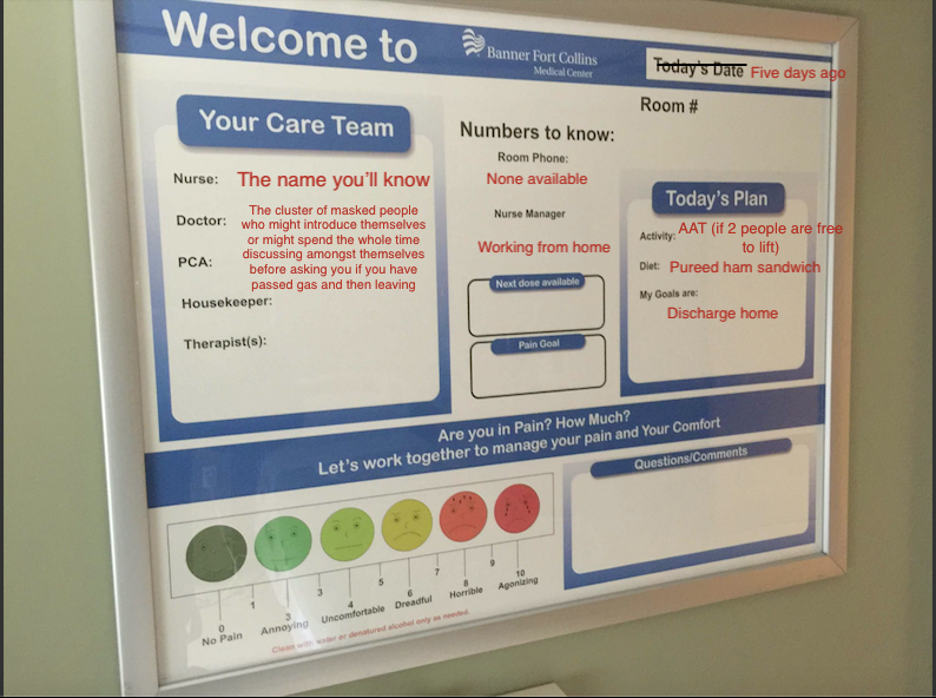

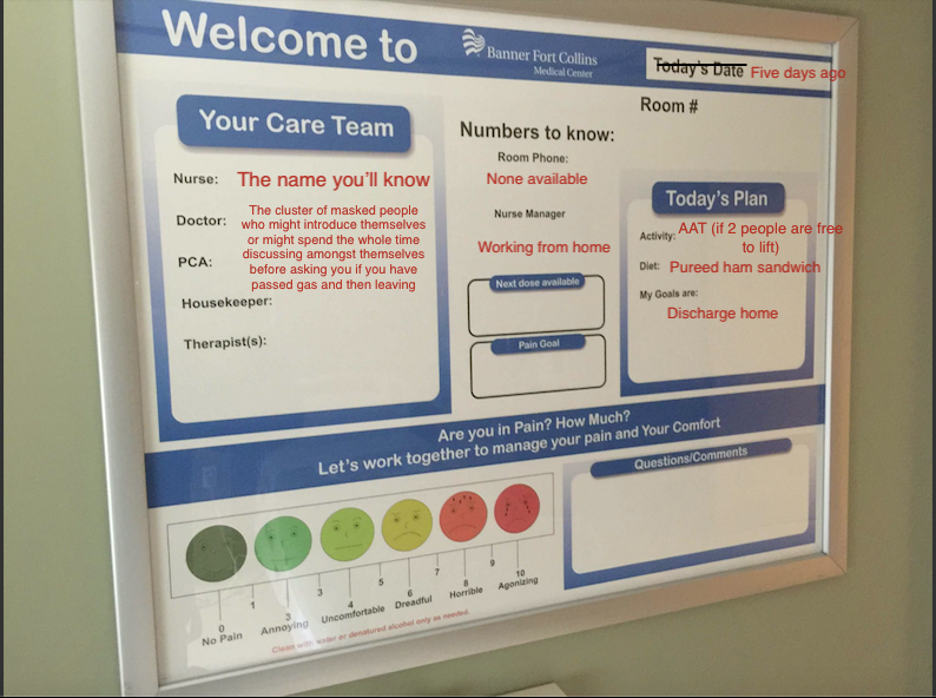

In our initial two humanism seminars, one particular anecdote employed by one of the patient educators to illustrate her experience within the hospital really stuck with me – she remarked upon how the communication board demonstrated the hospital’s attempt to provide a patient centred experience, and the ways in which that attempt fell short. Throughout my surgical rotation, I found myself paying close attention to these communication boards and found myself at times disturbed at how little effort was paid into the accuracy of these tools. In particular, I was horrified by how off the dates were at times – which not only could further confuse disoriented patients, but also demonstrated how out of date a lot of the board’s information might be. In one of the worst examples, I noticed that the date on the communication board was 5 days before the current date, which served as the basis and inspiration for this creative piece.

Like the patient who emphasized that these boards demonstrated how “little the hospital cared about them,” I too reflected on these boards as a metaphor for the patient experience in the hospital itself, and the ways in which health care workers fall short of actually caring for the individual and focusing on that person as both a participant and a recipient of care.

(Lack of) Communication Board, 2021

Humanism – Art Reflection

Humanism – Art Reflection

Maimoona Altaf & Jenny Liao

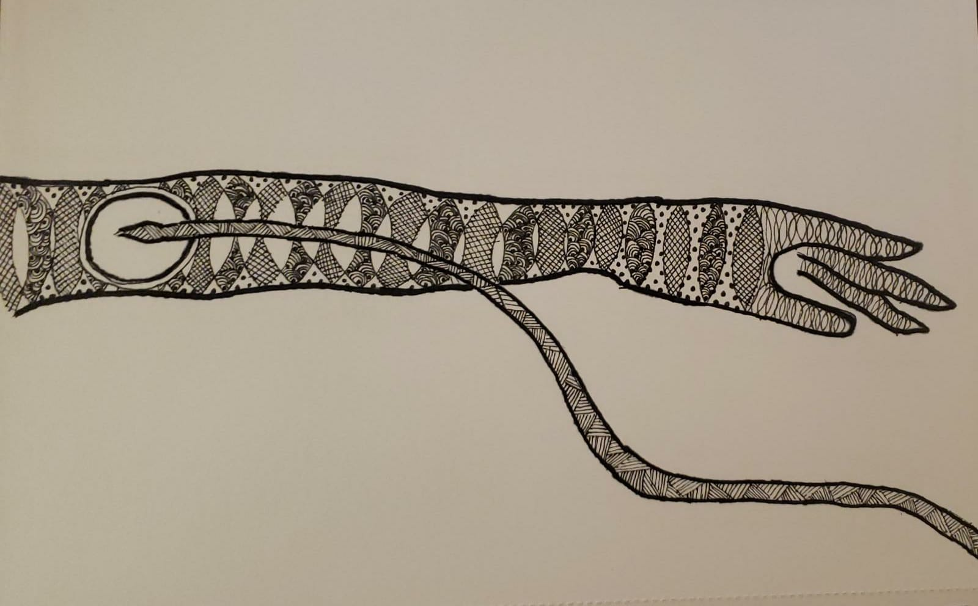

A Zentangle of a patient’s experience with an error in medicine and the holistic approach to her care that followed. A reflection on errors in medicine and forgiveness.

About Zentangle:

Zentangle is a form of art where the artist uses repetitive simple patterns to create an image, usually with black pen on white paper. Simply put, the artist creates a main border which can be any shape and within it, you add “strings” and create patterns guided by these strings. It has been used as a form of mindfulness based art therapy and form of meditation in the past as it has many key principles based on introspection that we used to reflect on our experiences as clerks during our surgery rotation.

Maimoona’s Reflection:

A key component of Zentangle is using a non-erasable black pen. The rationale behind this is the act of embracing mistakes and allowing for self-forgiveness. This concept encouraged me to reflect on errors in medicine and my own experience with this during my general surgery rotation. The incident occured with one of our patients who was pregnant and set to have an appendectomy. This, in itself, was a stressful case given the high risk of miscariage involved. Unfortunately, during the surgery, her IV went interstitial and she suffered from quite a painful cellulitis as a result. However, I think the way the anesthesiologist and surgeon dealt with this situation was quite commendable in that they were honest and upfront with the patient about this error, rather than trying to hide or dismiss the error. They instead took this as an opportunity to provide empathetic and patient centered care. They would routinely check up on her and provided her with the option of extending her stay at the hospital if she felt more comfortable doing so. Ultimately, although this error occurred, on discharge, the patient still felt like she received good care because her healthcare providers were honest with her and she was actively aware of/engaged in the course of her hospital stay.

Another key component of the zentangle process is admiring your art peace in a non-judgement, kind and forgiving way on completion. I think it is important to remember that as healthcare providers we are still humans and mistakes are inevitable. As long as we are honest and learning to grow from them, we should give ourselves the space for reflection and forgiveness. Without this, we can ultimately become burnt-out and even resentful. Therefore, I believe it is utmost important to remind myself of these aforementioned principles of Zentangle as a clerk and future physician.

Jenny’s Reflection:

During my general surgery sub-rotation, I met a patient with Crohn’s disease who presented to the hospital because of worsening symptoms. Our surgery team was consulted because she was not responding to medical management and was therefore being referred to explore surgical options. Our team assessed her and believed that she would be a candidate for surgery. We explained the procedure to her in regards to needing to resect part of her bowels and creating a stoma, and she consented to the surgery. Her surgery went well with no complications and limited blood loss. For our team, the surgery was a success. However, in the following days when we checked up on our patient, we noticed that her mood was low. We found out that she was having difficulty coping with her new stoma. This prompted us to consider possible supports that can help her with this transition including involving a social worker. I think this experience highlights the importance of remembering that our patients are not just a body of organs but they are people filled with complexity and have hopes and feelings. This idea is reflected in our zentangle drawing where small simple shapes put together are transformed into an intricate artwork.

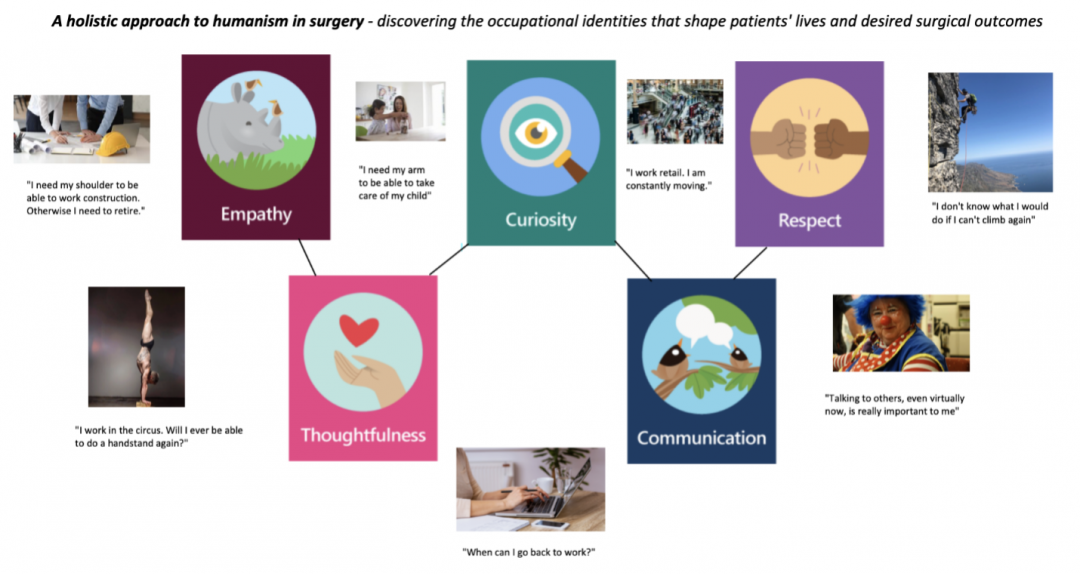

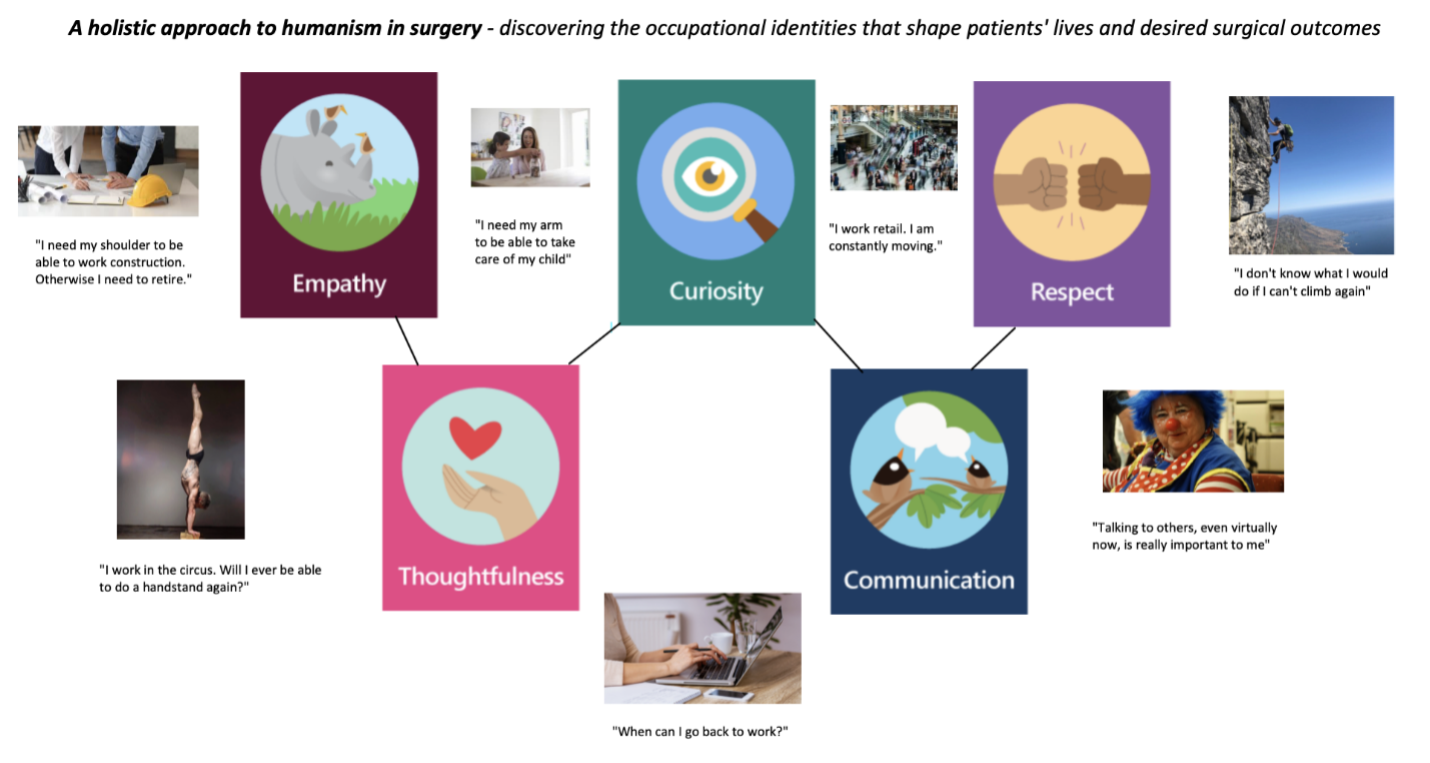

Ivona Berger

My piece is about the importance of using empathy, curiosity, thoughtfulness, respect, and communication to learn about what matters to a patient. In particular, I was reflecting on the significance of occupation. In the previous seminars, we discussed how sometimes surgeons did not take the time to learn about a person more holistically. I thought about my own MSc work where I investigated the needs of cancer survivors when returning to work and how their job was such a big part of who they are. Therefore, I was pleasantly surprised when my preceptor told me to make sure to ask patients what they do for work in order to form a connection and learn more about what is important to them with regards to their surgical outcomes. These are some examples that I remember hearing about from my patients during my surgical rotation. In some cases, we were able to address their concerns, and in others, we had to do our best to make sure we were honest with them.

Ivona Berger

Adrian Witol

Pictured is a crocheted piece that has unravelled and frayed at one end. My surgical service delivers an inordinate amount of unexpected terminal diagnoses, and I have watched many patients (who came in hoping for a surgical cure) learn that their time is very short. These patients are usually matter-of-fact with us, but after we step out of the room, I have heard many struggle to deliver the news to their loved ones over the phone. I am still learning how to hold space for these patients without unraveling myself.

Adrian Witol